Some of my friends are brilliant at curating social media feeds. They draw image and text together skillfully to represent important life milestones and their personal values, yet conceal the rest of life’s messiness. I find that so admirable; but it’s not me.

My Facebook and Instagram feeds are a mix of happy snaps, pretty landscapes, and objects… general chaos. Photos at bad angles mark great moments; but if you’re a true friend, we’ll likely eat cheese, discuss the world’s major problems, laugh at ourselves, finally yell “I really have to go now!” … leaving no photographic record. Or I’ll fail to post.

Through each life stage, I wrote. Badly, mostly. I guess at times I’ve written okay.

I’m not claiming to have command of the comma. That’s something kids growing up in the 80s in Sydney failed to learn. Turns out, some suit in the Education Department wanted to empower the former British colony — at the cost of the country’s grammar for about a decade. If you know, you know.

No, I’m not proud of my writing. But I’m grateful it helped me process eras of my life within community.

Blogging helped me after I quit my political economics honours degree to serve my Pentecostal youth group (at the encouragement of the worship pastor). It helped when I stopped writing worship songs for megachurches, frustrated that I somehow never had the reference CDs or invites to pool parties to discuss new hot sounds for the global church. I realised I’d done way too much photocopying for charismatic boys who were off surfing. Writing gave me words to describe Pentecostalism to my MPhil supervisor at the Australian Catholic University and engage the critics of “Jesus is my Boyfriend” music. I wanted amnesty, but there was no middle ground. So, I created my own organisation to work with those who served youth, and marginalised groups such as refugees, and Pentecostal churches in Southern Europe. I spent as much time with Christian development workers and justice-oriented folk as I could.

Writing gave me outlet while pastoring the creative team of an urban multi-ethnic Pentecostal church, navigating the challenge of a liturgical space serving Asian and white Australian communities. Writing helped me decompress and articulate the mixed commercial and spiritual interests I saw vying for Australian Pentecostalism.

Writing continued as a form of expression while I was in Los Angeles completing my PhD in theology, anthropology, and development studies; it allowed me to describe experiences in Pentecostal churches with Aboriginal Senior Pastors across three states of Australia. It helped me reflect deeply on what I’d listened to, and amplify people who greatly deserved applause; with the intention that others could take it much further. I wrote while involved in disability research at the University of Sydney, learning my neighbourhood better, and seeing people with intellectual disability speak back to (and become) the organisational leadership.

Then, I agreed to stop publishing by accepting a teaching role in the higher education awards of the megachurch.

It wasn’t quite as simple as that, of course. In my confusion, maybe also a form of resistance, I left the blogposts up, kind of like over-dried laundry on the clothes line. I didn’t want my identity to disappear.

By then, the church had grown to a “gigchurch” with over one hundred thousand people. I taught the social justice unit and supervised research. Once leaders were held to account, everything imploded. I certainly haven’t processed it properly; I may never be able to. But some really great feminists asked to collaborate, and I wrote to amplify (some) women’s experiences of that time. I now collaborate with scholar-practitioners in the Master of Transformational Development as they serve communities.

The special people who bore with me through these significant periods know I tend to be an open-the-fridge-and-pull-out-ingredients kind of author. I haven’t made it easy for those seeking black and white statements. In fact, I made some people mad. I had great conversations with others.

Looking back, I wrote the most random things: about visiting family rebuilding the Pacific after war; thoughts on why people leave the Australian Christian church; benefits of urban organic vegetable cooperatives in Los Angeles; being Pentecostal and figuring out Popes and Catholic Social Teaching; inspiring messages in really good movies.

It was all still up.

Until today, when I watched a show on home organising. A simple phrase made me open my WordPress and “Send to Trash” two hundred and thirty six published posts.

You’ve no idea how fantastic that felt.

What was the single phrase of inspiration? It was the silliest little thing.

It was this: “It will get worse before it gets better.”

The show starred an average middle class American who narrated their experience pulling out all their belongings to sort them, and put them back in better ways. The project revealed mayhem. Ten mayonnaise jars. A box of weird plugs and cords from old phones. A miniskirt fresh from the shop never worn. They grieved the lack of use of these items, and bad choices they’d made over the years. They made a decision to do better, and committed to continue on the way. It’s all a bit cliche, and I’m not sure I know how to stop the ideation.

But it made me think a bit about what inspires me now, after everything; what is worth keeping in the cupboards, so to speak. What is behind my belief in God, but also democracy, and good leadership during an age of Christian nationalism. Recently, someone asked why I believed, and I said “Montmartre” but I didn’t explain it well. So here it is.

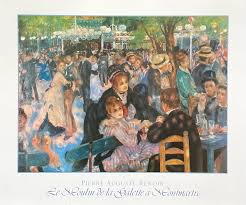

Montmartre is a very well-known neighbourhood; it is the 18th arrondissement on the right bank of the River Seine in Paris. It’s generally on tourist bus routes because of its art history. For example, Renoir’s famous images such as Bal du Moulin de la Galette (1876) depict community outdoor gatherings of working class people dancing during seismic economic shifts and the difficulty of the second industrial revolution.

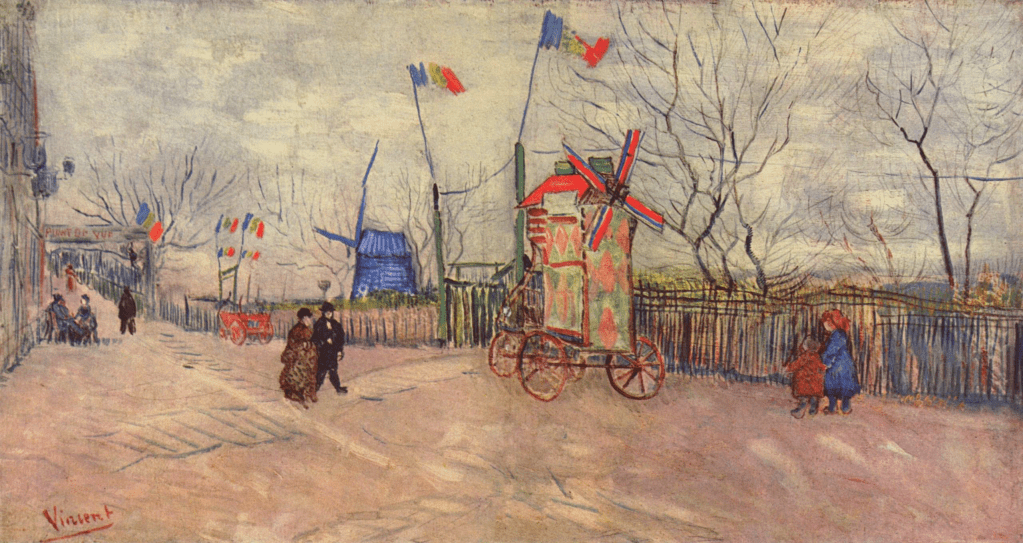

Similarly, Vincent Van Gogh painted there in 1886, depicting life just beyond the French city, experimenting with the different techniques that made him the master known today. His images of windmills and agricultural French life are now iconic.

Picasso joined the makeshift studio Bateau-Lavoir (“washhouse boat”) in 1904 where he painted the fascinating Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and other important pre-cubist works. At that time, he was penniless; Montmartre was a shanty town with big ideas and shady nightlife. Ironically, this piece is thought to be worth $1.2 billion today.

There’s no evidence of these three artists knowing each other. Just layers of history.

Under this romantic and slightly grimy French art history lies the struggle of the Parisii. It seems the Romans “established” the city of Lutetia in 52 BC after conquering an ancient Gallic tribe at an important trading junction. In this era, Montmartre was a Roman temple for Mars the god of war, who was believed to have assisted the city’s conquest. During the Empire, it is where the first Christian bishop Denis was killed, leading to Saint Pierre’s “chapel of martyrs,” (hence the name Montmartre) where St Ignatius of Loyola famously took a vow of poverty, chastity, and service with six university students, founding the Jesuit order.

Atop the summit of the highest hill in Paris, the beautiful Sacré-Coeur Basilica was built as an atonement for moral depravity.

And one random day, I made my way to the top of this hill, to order a nutella crepe. Sitting there, I realised I was slightly late to the Readings Service. I watched as ladies in white robes finished Vespers and silently walked across the floor. Most had left, but I watched one nun linger back. Quietly, as tourists sat in large noisy groups, she leaned over and lit a candle.

The symbolism of it all is a moment I will never forget.

Because women have always been in the Christian church lighting a candle on top of layers of war and poverty, inspiration and pain. If that doesn’t attest to something tangible and something good, then I don’t know what can.

Since then, I’ve found out that Sacre Coeur has a 135 year-old unbroken prayer chain. Its website states “this place is first and foremost a shrine dedicated to the goodness and tenderness of Christ’s heart.” And that is what I felt.

During the French Revolution, there was an attempt to stamp out devotion and replace it with reason. Marie-Louise de Montmorency-Laval, the last Abbess of the Benedictine order was beheaded on Montmartre during the Reign of Terrors.

It’s easy to consider faith simply emotion. Still, emotion is one of the ways humans know. Through it, we sense the real, the beautiful, the good, the true — and its opposite. Dismissing it is a gendered way of speaking about knowledges; as in, the logical is cast as the important realm of men, while women’s knowing is mere sentiment, as though it is not “enough.” But what I saw was one woman’s act of love.

It’s true I may not know the full history of Paris, or God for that matter, very well — except for the very deep sentiment of it. But on top of the remnants of all these complicated things, we can choose to light a candle of love. That choice only seems possible because of something outside myself. Faith is a gift which I don’t understand completely.

As the night comes softly, may you find me lighting a candle. The light of love still shines in the darkness, and the darkness cannot overcome it.

It’s a strange way to get there, I’ll admit, but maybe some of us walk strange paths to get to the same place. We might as well walk together where we can.